Two Saturdays ago Caitlin and I took a train from Prague to Beroun, hiked some 15 kilometers or so to Karlštejn castle, and then took a train back to Prague.

Train

Prague’s main train station is only a few minutes away from our apartment, it’s just on the edge of the tourist core of the city. There are a ridiculous number of trains and train routes. It’s also comparatively very cheap; for all our tickets we spent something like a total of $12 US for about a forty-five minute ride each way.

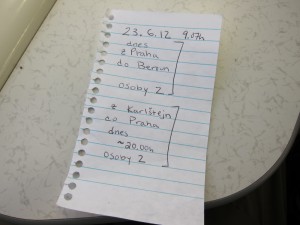

One thing we are big on is writing down exactly which tickets we want and just handing that paper over to the ticket teller. Beroun and Karlštejn turn out to be pronounced more or less like what an English speaker would default to, but many other placenames bear little resemblance to an English phonetic reading. English is very common in the big scheme of things, but not prevalent. Even with all the international travelers at the main station you can’t rely on easily asking for a two person discounted ticket, the express train, or whatever. So Caitlin looked up and copied down all of the wording on the train system website.

Svatý Jan Pod Skalou

In Beroun we had a three hour detour to watch the start of the Beroun Bike Weekend. From there we hiked to Svatý Jan Pod Skalou, St John Under the Rock, a modest monastery and the small village surrounding it. There is not much going on here beside a restaurant or two and the elaborate monastery chapel(s), but it has a great view walking into town.

Red Trail

From there we hiked over to Karlštejn. The Czech Republic actually has a really impressive national trail system. There’s a wide ranging network through the woods and countryside that is marked all the way into the villages and even towns, usually to train stations. We could have picked up this trail right in downtown Prague somewhere and walked dozens of kilometers all the way down. The trails are very non-technical and open, so it’s also very feasible to ride a cyclocross, mountain, or beefy touring bike all around on them.

Hrad Karlštejn

The castle (hrad) was built by Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor, to hold the crown jewels and important holy relics. Of the latter, many of the paintings actually have little sockets cut into the frame to hold bones, spearheads, and other bits.

Like a lot of the major castles here, this one saw its fair share of fighting, particularly around the Hussite Wars. It’s interesting looking at different renovations and additions to the castles. Many features that look like serious castle business are post-renaissance or even more modern renovations and actually make less sense for the real purposes of the castle. For example, the main buildings in Karlštejn are three distinct, separated towers in a progressively important sequence: The Imperial Palace, the Marian Tower, and the Great Tower. There’s actually no way to get into the last two from the ground floors, you have to go through the previous towers. In a post-renaissance update the first two were connected by nice little stone archways. When the castle was still important though as a physical defense they were connected solely by covered wooden bridges, like the main tower still is, so that you could easily burn the bridges down and completely isolate the tower(s).

Looking down the depth of the well required to go all the way down through the hill to the water table is also pretty neat. Wikipedia has an interesting tidbit about the well here being a significant weakness as it couldn’t supply enough water for a prolonged siege and all the miners being allegedly murdered to keep that a secret. Castle dudes also clearly loved tall, steep steps and nothing else. Daily chores could not have been pleasant for short people.

Getting inside the Marian and Great towers require a tour booked in advance, ostensibly to limit traffic through them; Karlštejn is one of the busiest tourist sites in the country. The first tower though has regular group tours (required to get in) and is worthwhile. I particularly enjoyed the vast, tangible difference between the bright, open assembly room with its kitchen area, large fireplace, and big tables, and the very dark, claustrophobic appearance room, where two tall, narrow window columns beam light onto the subject appearing before the king while he himself sat in a throne, the only piece of furniture in the room, set between the windows so as to be completely obscured in shadow. The tower entrance is also neat in that it’s essentially a locker room for the region’s knights vassal, with personal chests along the walls with their individual heraldry and space to bed down if necessary.

The village immediately outside the castle is small despite being a tourist hotspot. Entertainingly, as a prime national tourist spot, most of the restaurants have thick books with menus in every conceivable language. I would have to think a fair bit to confidently list more languages than some of them have. Vegetarian options were thin as the restaurants served mostly standard Czech fair, essentially pork knuckle or beef goulash and a kind of funny moist, dense, bland potato bread roll that’s really common here. However, we did find some omelettes and potato pancakes. Food seemed shockingly cheap for a major tourist area. We figure restaurants in Prague, outside of the critical centers of the tourist areas, run about 3/4 to 2/3 of what we would figure on paying in Philadelphia. Here was down around 1/2 to 1/3.

Train

The train from Karlštejn is just a few minutes’ walk from the castle. With both the forest trails and several bike routes along the Vltava and Berounka rivers to town, it’s clearly a popular place for people to ride to and then take a train home. Lots of cyclists were doing so when we were there. Trains seem largely very accommodating of bikes, even at peak times. Many cars have a few hanging hooks, and bigger trains have cars with large, dedicated rack spaces.